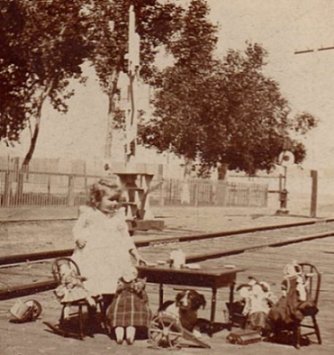

Milly Douglas-Pennant, Manolo and Lucia

Photo: Andrew Crowley

"Without a double lung transplant young mother, Milly Douglas-Pennant, a cystic fibrosis sufferer, will not live to see her baby daughter, Lucia, grow up." Elizabeth Grice

Who will give Milly the gift of life? By Elizabeth Grice

The mother propped up on pillows with her baby by her side is waiting for someone to die. Breathing is difficult, even with the help of nasal oxygen, so her sentences are short, punctuated by quick, sharp coughs. Her hospital bag has been packed for six months. Her husband has given up his job to care for her and their one-year-old daughter, Lucia. Her parents are ready for the telephone call that will summon her to Harefield Hospital for a double lung transplant operation. But as the days creep by, Milly Douglas-Pennant's bright spirit, and the energy she has poured into defying cystic fibrosis (CF) for so many years, is becoming harder to sustain. Doctors say her medical situation is now "desperate".

"I've just got to hold on," she says. "I don't feel excited about it any more. It is so monotonous. The waiting. I wonder how I can possibly get through it… how long it will be. There are times when I get depressed. Other days, I think I can do it."

"I find it hard to imagine being able to do normal things. The more time goes by like this, the harder it is to remember. Manolo [her Spanish husband] will paint a scene for me. 'Imagine we are walking along a beach', he'll say. I can't imagine walking along a beach and not being breathless. Manolo has probably forgotten what normal life is. I worry about him if it all goes wrong. I worry about what he's going to go through. I think of time stretching out ahead of me, just stretching out."

She is still hopeful, but those around her see that she is sinking for want of a transplant donor and they feel helpless. Lucia is the joy of all their lives. The fear no one mentions, underlying everything, is that Milly, 29, may not see her grow up.

Until her pregnancy, Milly had never allowed cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder affecting the lungs and digestive system, to get in the way of what she wanted to do. The progressive disease causes the lungs and pancreas to secrete a thick mucus that blocks passageways and, over time, irreparably damages the lungs. With drugs, physiotherapy and nutritional supplements, Milly had lived a "normalish" life. She travelled the world, bungee-jumped, lived in Spain as a teacher and fell in love.

When Manolo Garcia Falcon, a pilot, asked Milly's father for her hand in marriage, as he believed was the English custom, Paddy Douglas-Pennant replied: "Yes, but only if you look me in the eye and tell me you totally understand what you are taking on."

What he meant was that Milly, then in her mid-twenties, had already lived longer than many people with cystic fibrosis. Fifty years ago, children with CF rarely survived beyond six. Now, as treatment advances, more than half live past the age of 31 and many beyond 40. Milly's elder sister, Anna, had died of the same condition, aged only 14, in 1993. The family was further devastated in 2004 when Milly's younger brother, Johnnie, a gifted boy who suffered from dyspraxia, drowned, aged 17. (Dyspraxia is a motor learning disability that can affect movement and coordination because brain messages are not properly transmitted to the body.)

With Latin intensity, Manolo assured his future father-in-law: "It is my destiny." They married in 2006 and, two years later, she became pregnant. Pregnancy makes big demands on women with CF, though some come through it without too much difficulty. Milly became so weak and breathless, she could hardly stand. "Her batteries were so low, says her mother, Sarah. "We did not realise quite what a risk the pregnancy was."

Lucia had to be delivered by Caesarean section nine weeks early – a prematurity that almost cost her life. But the birth didn't arrest Milly's decline. In August 2009, she almost died from CO₂ poisoning because her lungs were unable to expel used air. It was a big setback, from which she never fully recovered. In September, she was put on Harefield Hospital's waiting list for a double lung transplant. At Christmas, air began to leak from her lungs into her chest wall, requiring major surgery. Again, she almost didn't pull through.

"When they first mentioned a transplant, I was horrified that they thought I was ill enough,Milly says. "For two months, I fought it. Then one morning in April I woke up and was absolutely sure that I wasn't going to get better till I had a transplant. I felt it couldn't come soon enough."

The Douglas-Pennants converted one end of their Georgian home in Wiltshire into accommodation for Milly, Manolo and Lucia. With the meticulousness of a nurse, Sarah sets out her daughter's arsenal of drugs and syringes on a large tray. This current phase of her medication, morning and evening, takes an hour to prepare and more than an hour to administer. "It takes all day just for Milly to have a day," says her mother.

"I have a high-calorie diet, but I still lose weight," Milly says. "I burn up so many calories just staying alive. I'd happily never eat again, but I'm permanently trying to force down a morsel of food. I'd love an apple sometimes, but I think, I'd better have a cake.' "

Her mother notices how loose her clothes have become and how she has developed the walk of a person too weak to bear her own weight.

One of the many ironies of Milly's situation is that she had fiercely longed to be a mother and yet is not strong enough to dress, wash or feed Lucia. "I do nothing for her,she says. "They bring her to me and put her down on my bed."

Despite her weak hold on life, she does not regret deciding to have a child. "Even knowing what I know now, I would do the same to have Lucia. I might have been heading for a big downturn anyway. We will never know.

"Maybe if I had known I was going to end up like this, I might have wanted a surrogate mother to carry the baby. Is that possible, or is it just something that happens in magazines?"

Milly has a big circle of friends. Two of them have started a rolling email campaign to encourage people to register as organ donors – currently the subject of an NHS initiative.

"It was born out of a desire to do something for Milly," says Katie Elliot, 29, "and to make people aware of the pressing need for organs. To register is such a small but potentially life-changing step. It takes less than two minutes. Most people say they are in favour but few do anything about it.

"It is unbearable to watch someone you love suffer. Despite her illness, Milly is an irresistible character. She has such a non-defeatist attitude. Before this, you would never have realised she had cystic fibrosis. She is very strong and determined – that is why she's had the life she's had. For someone as nurturing as she is, being a mother is paramount to her. Lucia has brought so much joy.

"But no one is under any illusions. We all know how precarious her situation is and how badly she needs these lungs, Kate adds.

It is humbling to see the Douglas-Pennants fortitude and practicality. Already battered by tragedy, they face the possible loss of their third and last child. Yet they are dedicated not just to keeping Milly alive long enough to receive new lungs but to improving organ-donor rates for everybody.

They contacted Reg Green, the organ-donor campaigner, after reading in these pages last month how his son Nicholas's organs had transformed the lives of seven people. Mr Green advised them to tell The Daily Telegraph about Milly's urgent need for a lung donor. Although 90 per cent of the population supports organ donation, 40 per cent of families say no at the critical moment and only 25 per cent sign up to the Organ Donor register. Sarah Douglas-Pennant says that, although there are now transplant coordinators in all major hospitals, not enough is being done in intensive-care units to get the message across.

Because she could not face the idea of donating her elder daughter's organs – Anna was too ill for a transplant – Sarah understands the deep inhibitions some relatives feel when they have just lost a loved one. "After Anna had suffered so much with cystic fibrosis, I could not bear for her to have anything else done to her. But if I had been skilfully told about the huge bonus to the recipients in a way I could have related to, maybe I would have conceded.

"It is a high calling, to be able to deal honestly, tactfully and truthfully with grieving relatives. It requires very careful training as well as a deal of natural charm in the person making the approach."

Now she sees the gift or organs as potentially the one good thing to come out of a terrible time. "While they are alive, you are trying to protect this precious person. But the minute they are dead, they are gone. The body is a shell. You have no need of that shell. But others may have."

Dr Paul Murphy, the Leeds consultant who is leading the Department of Health's current campaign to raise organ-donation rates by 50 per cent within five years, says family consent is the biggest obstacle to donation in Britain. In approaching relatives sensitively, timing is vital, he says. "There is no point in broaching donation if the family has not accepted the inevitability of death, and those who make the request must have the time that families need."

He believes donation should ideally be based on the wishes of the patient and presented as part of end-of-life care. "For too long we have apologised for bringing up donation with a grieving family. We have presented it as something we inflict on them rather than as an opportunity for a family to realise the most honourable wishes of a dying loved one.

"Clinical staff need to be more sensitive about when is the right time to ask a family, and be trained to use the right words and have the right knowledge, but perhaps we all have a responsibility to make it easier for our families – by getting on to the NHS Organ Donor Register and by telling them that we have done so."

For Milly herself, the issue is reduced to its essence. The lungs she is waiting for will be inert organs taken from someone already dead but they could transform her life. "I don't think about the poor person who has to die. I just think of the lungs I need. I get through each day, each week. It's not living. It's existing."

Life is precious

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9frmZcFUgdA&NR=1&feature=fvwp